By Clara T., Claire B., Zahra A., JaeHa (Justin) K., Bryan R.V., & Mai E.L., with the staff of the Princeton Summer Journal

SUN Meals, a federal program that provides no-cost meals for kids during the summer, are inconsistent across the country. Are they truly meeting food security needs?

Layers of stacked frozen leftovers saved from dining halls—mashed potatoes, mac and cheese, and salads—in Ziplocs. School lunch plates filled with tan and brown foods, with little to no green in sight. Scrambling to figure out the latest EBT eligibility. Staring at an empty fridge on a hot summer day. Students of all ages, whether K-12 or college, continue to face hunger and a lack of accessible nutritious food, these are just some of the many ways that food insecurity manifests for students and families.

“The issue goes beyond just someone [having] enough food to meet their calorie needs, fill their stomachs, to ‘are we meeting the nutritional needs of a person?’” said Dr. Lauren Dinour, faculty member at Montclair State University with the Nutrition and Food Studies department.

Having access to nutritional food helps children develop healthy habits so when they become adults with greater freedom, they have those skills established. As Mykaila Shannon, the Health Promotions Manager at Princeton University said, “when it gets in early, it gets in deep.”

A Princeton Summer Journal investigation reveals how SUN Meals—a federal program that provides meals and snacks at no cost at various neighborhood locations—fails to provide nutritious food for children on a nationwide scale. This presents concerns not just for young people during the summer, but is indicative of systemic failures to provide all people easy access to proper nutrition.

The investigation sampled 65 sites and 50 meals across the United States. For each site reporters visited or contacted the organization and recorded the meals being offered and the state of the site. The Journal found great inconsistencies in the sites and meals across the country.

A majority of the sites were visited in-person. 51 percent of those served elementary school students, 40 percent families, 20 percent middle school students, and 9 percent high school students. In 20 percent of cases, the sites were empty other than the reporter.

The large portion of elementary and middle school students could be attributed to the summer camps who often used SUN sites for their programs. In some cases, the presence of only young kids and camps led investigators to experience cautious and confused staff when they tried to access the meals. 14 percent of sites visited had some type of cautious staff, 11 percent appeared understaffed, and 4 percent appeared to have inattentive staff.

While searching for sites, reporters often found the federal SUN database to be inaccurate and out of date. 10 sites had inaccurate contact information online, or were not contactable for other reasons (such as not including a phone number or email on their website), and even more were excluded from the investigation because the site had closed or didn’t exist.

While 60% of the sites were “easy to find” in-person, 29 percent of sites had no signage to locate them outside, with 11 percent of them described as “hard to find.” The lack of accurate information and difficulty to access sites, shows how unpredictable SUN sites are, making them an unreliable solution to food security.

To understand the nutrition of the meals provided at SUN sites, Shannon provides a simple solution—colors. Shannon describes how beige colors often reflect some lack of nutrition. She recommends that students, “throw some things in there that are colorful because colors often, you know, represent some nutrition.”

As she puts it, colors are an easy, gamified way for kids to be able to say: “oh, I ate four colors today at lunch. That means I had a good meal.”

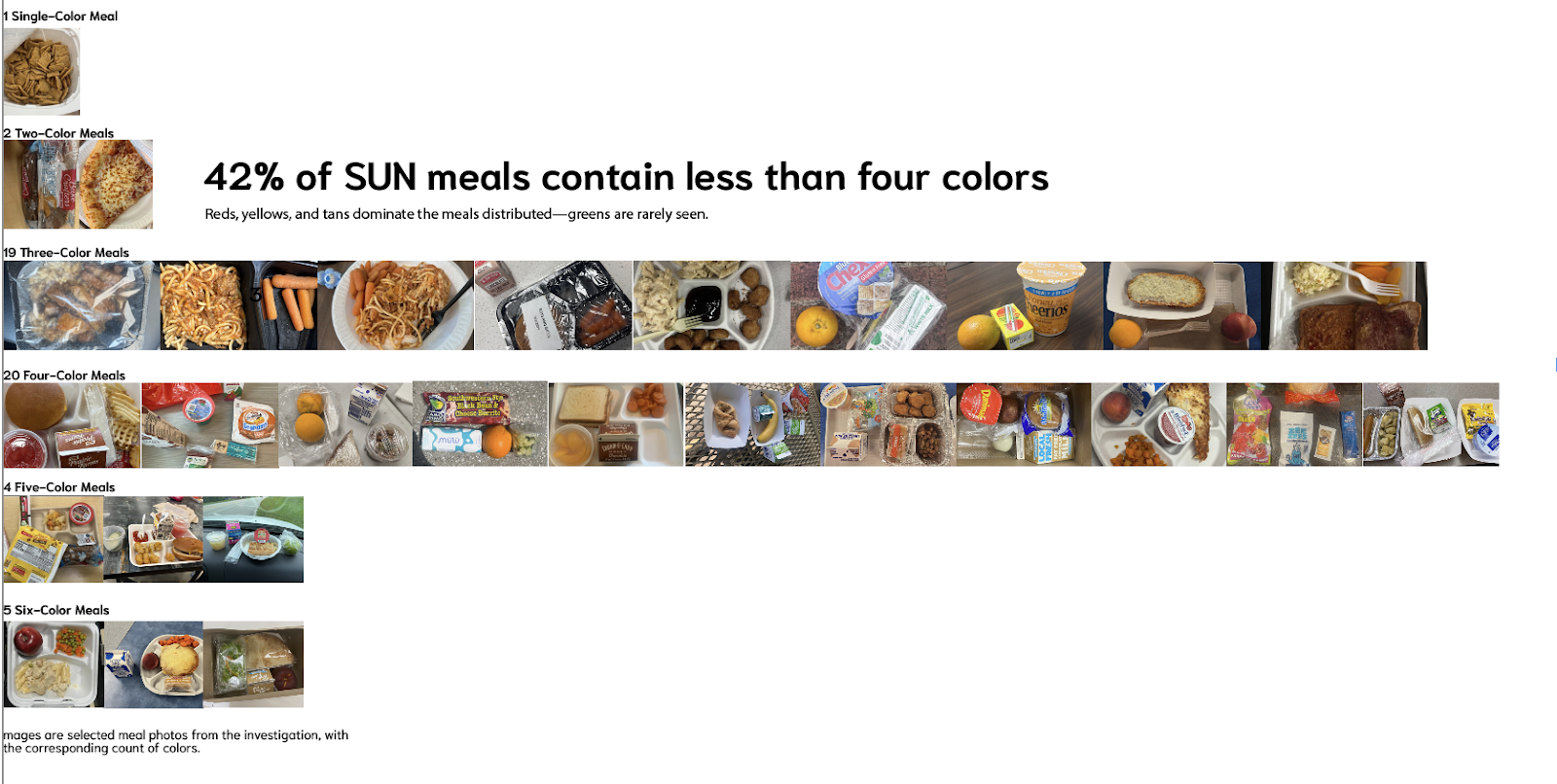

To explore this for SUN sites, the Summer Journal tracked the colors of food items given by summer meal programs: Grain forward items were categorized as tan, meat categorized as brown, mixed fruit cups and juice mixes were categorized as multicolor, milk and chocolate milk were categorized as white and brown respectively, cheese and egg as yellow, and vegetables and fruits were categorized by type into red, orange, green, blue, and violet categories.

Across all 65 sites, 94% of the meals served had tan foods, meanwhile, only 18% of meals had green foods in them. Moreover, 42% of the summer meals do not contain four colors or more.

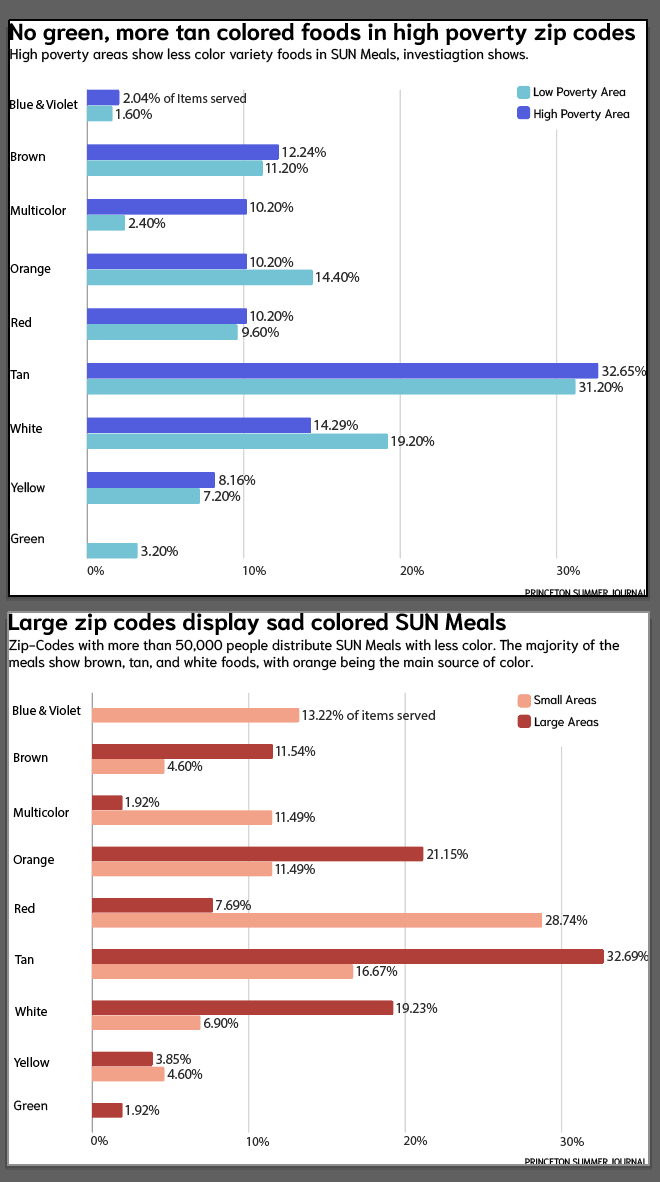

The Summer Journal also analyzed how the colors in summer meals changed depending on the demographics of the population, including, poverty rate, population size, and racial breakdown.

Findings showed that areas with 20 percent or more of the population under the federal poverty line had no green items, compared to 3 percent green foods in lower poverty areas. Zip codes with more than 50,000 people, provided 32 percent of tan meals, while small zip codes only recorded 28 percent. No significant difference was found between majority white and majority non-white areas, but the five sites sampled in high poverty, majority non-white, large zipcodes only had orange, tan and white foods.

While some SUN summer meal program sites are successfully providing meals, many have failed to provide proper nutritious food. On a nationwide scale this unreliability presents concerns for kids without food security.

The inconsistencies among summer meal sites extend beyond the SUN meal program. Summer EBT and SUN Bucks give low income families $120 per eligible school-age child monthly for grocery benefits. However, as of August 2025, according to USDA, 13 states remain without federal money for the Summer EBT or SUN bucks after rejecting them, effectively leaving millions of eligible children without the benefits.

“So if we have states that are saying that they’re not going to participate, they’re not going to pay into these programs, then we’re going to have huge disparities in who has access to them across the country,” said Dinour, “and if we make some of these programs like SNAP, for example, have more strict eligibility requirements, then we’re going to have even less people participating”

Dinour explained that when benefits go up, food insecurity goes down. Giving people more money and food means they will have more food to eat. She says food insecurity has had an uptick in 2022 and 2023 and imagines it’s going up as a result of tightening eligibility.

The solution to these problems begins with destigmatizing food insecurity in our everyday lives. Ricardo Kairos, a faculty member at Rutgers University specializing in Nutrition says that destigmatization encourages people to seek out resources rather than facing it alone.

Many Kairos interviewed for his work helping people get benefits, felt they weren’t entitled to get food assistance.They felt the food wasn’t for them and that they shouldn’t take resources from other people.

On some occasions, a singular word could change a stigma entirely. Mark Dinglasan, the Executive Director of the New Jersey Office of the Food Security Advocate (OFSA), believes that when it comes to mitigating the food insecurity crisis, it is imperative to accurately differentiate between “food security” and “food insecurity.”

When he first came to his office two years ago, Dinglasan commented that his first focus was on “picking the most holistic and comprehensive definition for food security that I could find.” At the time, his office was titled the Office of Food Insecurity — which Dinglasan was not a fan of. Eventually, Dinglasan chose to follow the definition of food security followed by the United Nations, and renamed his office to be the Office of Food Security.

Dinglasan believes that food security can only be truly achieved by focusing on helping people, rather than treating them merely as numbers. “Ending hunger has nothing to do with food,” he said. Rather, he believes, the focus should be on helping communities as much as possible.

Similarly, Chilton rejects the term “food deserts” because it falsely suggests that no food exists in certain areas. Chilton argues that the term “food apartheid” is more fitting because the limited access to healthy, affordable options in grocery stores isn’t an accident, but rather a result of an intentional decision shaped by food systems, zoning laws, public policies, and systematic disparities. Others argue the term “food swamps” for areas that simply have an abundance of non-nutritious food options.

The failure of distributed meals to meet the dietary restrictions, cultural preferences, and nutritional needs of people is why programs like SNAP and SUN bucks are beneficial, because giving people the money to choose what foods to purchase for themselves and their families can lead to meals better tailored to their needs, unlike school meals and SUN meals.

Still, Chilton argues that rather than relying only on programs like SNAP, which exist because wages are too low, we should raise wages instead. She suggests implementing a universal basic income (UBI) regardless of employment status would ensure nobody goes hungry, everyone has shelter, and people can afford necessities.

Another part of the solution is finding and supporting initiatives that ensure food gets to those who need it. There are many existing resources and initiatives that remain obscure to many. Free community supported agriculture (CSA) programs offer fresh food to lower income people and are often cheaper than grocery stores. Public insurance provides free nutritionists. Tiaa.org, provides a customized guide explaining what people’s co-pays, deductibles, and insurance particulars are. Planned Parenthood has a teen group that aids nutrition. Schools often have reimbursement programs to provide money for lunch or breakfast.

One initiative, the Food Recovery Network, is a nonprofit led by students with the dual mission of recovering surplus food and ending hunger, repurposing it and providing it to individuals who are food insecure.

Dinour is the faculty advisor for a chapter on Montclair’s campus, one of few New Jersey schools with a chapter. Initially, it was a class project by her students intended to address food waste then they began the chapter in 2017. Students essentially repackage safe, edible excess food that would’ve otherwise been thrown away, and place it in a fridge on campus.

According to Dinour, around hundreds of thousands of pounds of food have been recovered on Montclair’s campus and the number of visits to their fridges increased by around 1,500 visits over the course of the last year, adding up to almost 8,000 visits to the pantry from September to June.

“We’re doing a lot, we can do much more,” Dinour said. “But I don’t know that we’ll ever get to a place where we are eliminating the need for all of our students. And that’s hard to sit with.”

Methodology

METHODOLOGY

Princeton Summer Journalists selected sites nearby their hometowns to sample. For each site they either visited in-person, or contacted them virtually. For each site the reporters recorded qualitative observations and if possible the content of a meal.

The Princeton Summer Journal Data Team then compiled all the data reported and tracked qualitative patterns, like how busy the site was, who it served, and how easy it was to find.

Reporters then looked at meal descriptions and photos to determine the colors provided in each meal. Colors were grouped into: blue & violet, brown, multicolor, tan, red, orange, yellow, and green. Site demographics data such as the site’s zip code, population size, poverty rate, and population diversity—was joined with the color counts to uncover how the colors of food in each SUN Meal varied between towns with similar populations.