Maggie Salinas

Maggie Salinas

By Maggie Salinas

Sunland Park, N.M.

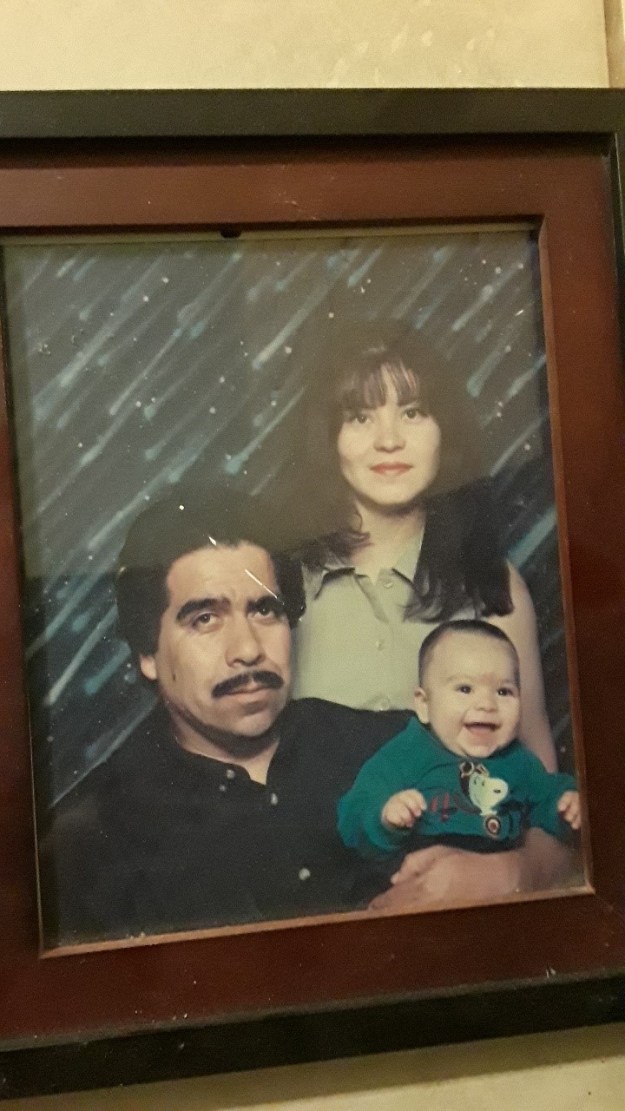

My father, Carmelo Salinas, immigrated to the U.S. in the 1970s after he couldn’t find work in Mexico. He was only 17, and he supported himself by picking pears in Southern California. We recently discussed how hard those early years in America were after he kept his experiences silent from everyone for years. Why did you find it necessary to immigrate for work?

“Mexico was corrupt and they didn’t want gente like me working. Everyone needed the money and was out to get you en Mexico. My dad used to be a bracero when he was young too, and he introduced my mom to American money.” What exactly did you work as?

“A lot of us usually worked in barracas de comunidad, and we would go up the mountains en Tehachapi [a city in California] to trim pear trees. Las barracas looked like prison cells. There [was] a two-in-one small bed, and we shared one toilet and a kitchen. Looking back, it was dangerous, but back then it was better than nothing.” Do you remember how much you earned?

“The owner would visit every quincena to pay us, 15 days. He would come up to you and go:

‘¿Cuantos arboles podaste, Carmelo?’

‘No pos’ que cien’

‘Bueno, son $150 por cien arboles’

He gave us about $150 per 100 trimmed trees every 15 days or a month algo así.” Did you face conflict with other workers?

“Sí, there were some old folk with us who didn’t want to go out and work with us because they had reumas, like arthritis, and they didn’t want to go out in the cold. Pero there were others who were just lazy. And they wanted us to split our earnings with them, or they would threaten to beat us. Some of us got into a fight with some of them. We didn’t want to pay them, and they tried stabbing me. I was able to take the knife away from him but your tío started punching him out of anger for threatening me. I remember telling him to stop so we wouldn’t get in trouble.” Was trimming pear trees the only way you earned money?

“No, after la temporada de piscar [harvesting] we would go to Bakersfield and lay down an irrigation system. We had to move pipes, and I remember when I had to supervise them at night, I would sleep under the water when they broke because the water was warmer. We needed to rent a place down in Bakersfield, and they paid me $3.25 per night. It was good money. We rented this house, and we had six Mexican guys, including your tío and me, and four girls. Some were American, and others were pochas, Mexican-American.” Did you have any encounters with deportation?

“Oh yeah. I used to have a girlfriend, her name was Suzy, but she was part of the pandillas, like gangs, in East LA, and I was really scared of the cholos. Fights would break down often when we went out to eat in her area, and I tried to get away, but one time la migra, immigration, came down and got us. They took us down to Tijuana. Sometimes they took [us] down to Calexico, Chula Vista, and Downtown LA for detainment. They would deport [us] in about 48 hours.” What did you do when you were deported?

Maggie Salinas

“I came back, por la familia.” Did you meet any interesting people?

“Cesar Chavez. I met him when he began his protests in Bakersfield, around 1973. Maybe it was just me, but I didn’t participate. To me, I felt there was no real gain in protesting other than attention, but I had more to lose. If I were older and had been educated past age 12, maybe I would have spoken to him more. A lot of us stayed away from the huelgas. We needed the money, our parents needed the money, and it was better than unemployment in Mexico. Uno tenia miedo de perderlo todo.”

“I was young, I only knew to survive. If I were educated, I think I would have appreciated the movement more. But I didn’t want to lose my progress in life. And he was famous, but I didn’t care to pay attention, but that was just me.” Today, Carmelo Salinas is a father of five children, all first-generation American citizens. He worked his way from being an immigrant in California to residing in Sunland Park, New Mexico. Born in 1955, he immigrated to California in the ’70s and learned English through pop culture. Though he didn’t receive his GED until 2014, along with his wife who was also an immigrant, he earned certification as a machinist and welder. He earned his American citizenship in the ’90s and helped his wife gain residency in 2007. To this day, he works endlessly to support his family, and contrary to harsh claims that date back to the ’70s, he never took advantage of welfare or the government’s re- sources without working. Although monetary wealth is not present in the family, love and moral values always are.

Former Vice President Joe Biden has failed to draw sustained excitement among younger voters. (Photo credit: Adam Fagen)

Former Vice President Joe Biden has failed to draw sustained excitement among younger voters. (Photo credit: Adam Fagen)

Nasim Almuntaser, a college student, has been working long hours at his parents’

Nasim Almuntaser, a college student, has been working long hours at his parents’