By Tahia F.

The Trump administration’s crackdown on illegal immigration affects millions of immigrants, including the 408,000 undocumented students at American colleges and universities. A.H., who requested to be anonymous, is a student at City University of New York, and Gabriela, who attends a university in Oregon, are just two of the many undocumented students who share this struggle. Their experiences paint a bigger picture about the association between immigration status and education in the United States.

Gabriela’s family uprooted themselves from Guatemala and moved to a majority-Hispanic neighborhood in Maryland when she was 13. She missed the leisure of playing soccer outside without fear of deportation. “I loved going next door and sitting there for hours until my mom picked me up, or playing with the kids in the neighborhood,” Gabriela says of her hometown in Guatemala. “I used to play on the dirt without shoes on. The football balls were made out of plastic, just plastic with air.”

In Maryland, she was surrounded by Spanish speakers, but having no prior English education, she was placed in specialized classes for English language learners.

The language barrier was just one of many obstacles in her path. But with the odds against her, Gabriela knew her dream was to help people in any way possible. This dream led her to take an interest in becoming a surgeon, however she ultimately decided against it. “You cannot ask for loans, you cannot ask for aid,” Gabriela said. “Most of the scholarships require status.” Ultimately, she was forced to reshape her dream, which led to her newfound interest in social work.

On the other side of the country resides A.H, a biochemistry major from Bangladesh. A.H. came to the U.S. unexpectedly five years ago with her two older siblings, leaving their parents behind. She planned to apply for asylum but that turned out not to be possible. “I was told I would be documented,” she says, “but that wasn’t the case.”

Similar to Gabriela, A.H. didn’t experience much cultural shock after moving to the U.S. The bustling city of New York reminded her a lot of her home in Dhaka. Her fluency in English and the rigorous education she received in Bangladesh’s school system helped her thrive in U.S. schools.

While both A.H. and Gabriela are striving to achieve their goals, they remain uncertain about their futures. Things for each of these students — financial stability, physical safety, job security — can change in an instant.

“Every year when I have to do the FAFSA it is scary,” Gabriela says, referring to the inconsistency of financial aid. “Okay, if this is the amount I have to pay then I am not continuing my education.”

A.H. agreed. “It’s kind of hard for me to envision a job job because I’m undocumented,” she says.

A.H., who is able to attend college with the support of a generous scholarship, hasn’t been deterred from pursuing her initial career choice: becoming a professor. It is more than just a personal goal. “The reason that we don’t feel seen is the reason that we try,” she says. “Where is a Bengali career woman? I think a lack of representation is a motivator for me.”

A.H. shows this dedication by volunteering with various political movements, including Desis Rising Up and Moving, one of the first groups to support New York City Democratic mayoral nominee Zohran Mamdani.

Gabriela, too, expressed a desire to help others. “I know that I have the potential to help people, I have always helped people and I want to work with them. I know that I could be an inspiration to the students,” she says. “I have that mentality that other people are looking up to me.”

Both students dedicate their time to support others in spite of the lack of support they receive themselves. “There’s no guarantee,” A.H. says. “If ICE shows up on campus, there could be a collateral arrest.”

The constant threat of deportation and loss of financial resources has taken a toll on both Gabriela’s and A.H.’s mental health.

“I don’t get any mental health resources or [support from my class],” Gabriela says. “When the presidential election was going on, it was a time when I really needed support. There were no ways for me to stay on campus.”

A.H. expressed similar concerns. “There is a lack of understanding on how faculty can support students. I’m tired of therapy circles, I need actual organizing efforts,” she says.

Despite the hurdles, Gabriela and A.H exemplify the courage, perseverance, and resilience it takes for undocumented students to succeed. Undocumented people are more than just statistics. By continuing to pursue their dreams in a system that works against them, they challenge narratives that reduce them to numbers.

Gabriela and A.H. are just one part of a larger story, as undocumented students continue to rise above intolerant policies to keep learning and accomplishing their dreams.

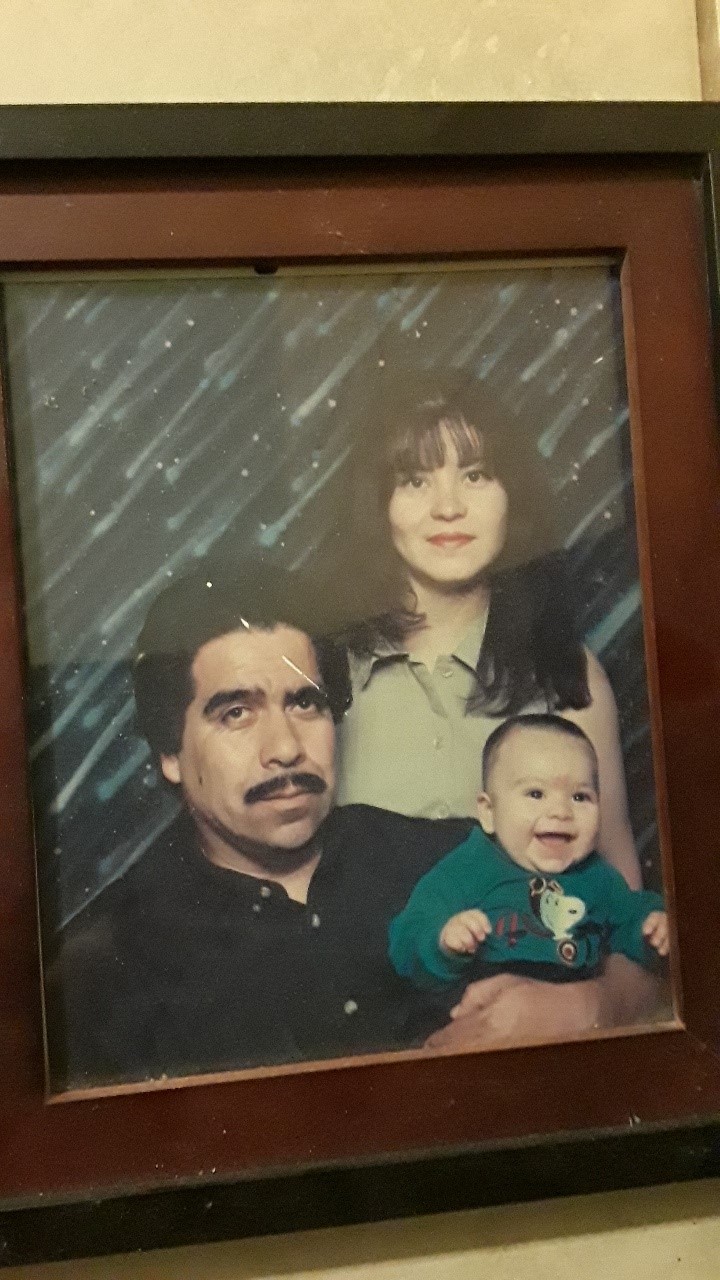

Maggie Salinas

Maggie Salinas